Settlers began arriving in the Edmonton area in increasing numbers in the 1880s. Several communities were established, the largest being Edmonton and Strathcona. As separate towns, naming was done independently.

An examination of these two early maps shows how confusing the issue was. Strathcona used a quadrant system, with the centre being today’s Whyte Avenue and 104 Street. Edmonton’s system was more complicated. Streets were numbered from 1st street (today’s 101 Street) heading west, while names were used on streets east of 1st, and on avenues. Of the named streets at this time, many either described the area (Cliff Street, Coal Street), or paid homage to early land owners (Kirkness Street, McDonald Avenue, Fraser Street and Sinclair Street).

By the early 1900s thousands of people were coming to Edmonton in search of a better life. As a result, land speculation was rampant. Investors purchased large parcels of land, subdivided them, and sold lots to newcomers. New subdivisions sprang up almost monthly, with monikers such as Fernwood, Ascot Park, and Eureka. These names were used as marketing techniques to entice would-be buyers to the area.

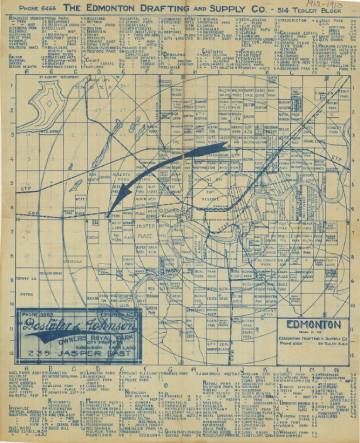

Edmonton Subdivisions

Edmonton Subdivisions, ca. 1912 [EAM-13]

This map from 1912 shows the subdivisions which had been created. It is important to remember that most of these communities existed only on maps - they were the hopes and dreams of optimistic land developers who purchased the areas with plans to cash in on Edmonton’s boom. When the market crashed the following year, many of the developers lost everything, and the areas remained rural for decades to come.

Naming Schemes

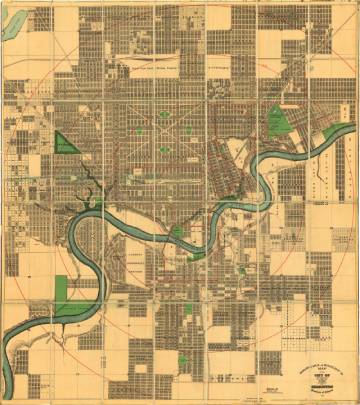

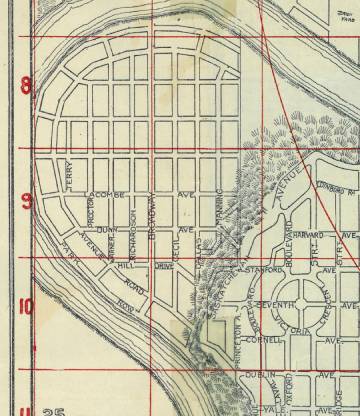

Driscoll & Knight’s Map of Edmonton, 1912 [EAM-86]

This map of Edmonton shows the state of naming in Edmonton at the height of the boom. Developers had been busy buying property and dividing it up for eager investors. Similar to the community names, the streets and avenues were named by the developers as a way to market their properties. By looking at the map, we can see some of the naming schemes that were created.

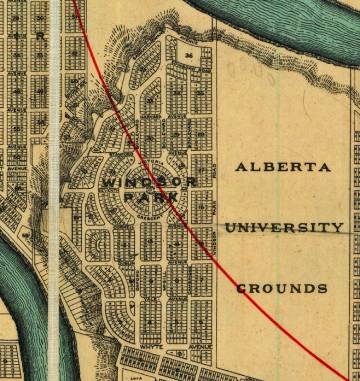

Names like Yale, Harvard, Stanford, Oxford, Cambridge, and McGill were a nod to their proximity to the new university, and the area was clearly marketed towards people from Eastern Canada and the United States, as well as the United Kingdom.

North of downtown and east of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway (between 120 and 121 Street), avenues were named for rivers: St. Lawrence, Albany, Muskoka, Nipigon, Brazeau, Stikeen [sic], Okanagan [sic], Yukon, and Pembina. West of the railway the avenues were named for trees: Pine, Elm, Spruce, Willow, Oak, and Beech. Around the subdivision of Industrial Centre (now Delwood) the avenues were named for animals: Cariboo, Buffalo, Beaver, and Elk.

Other developers used the names of places, which might have been familiar to buyers, or perhaps inspirational. Jasper Place (now Crestwood) used the names of North West Mounted Police forts (Calgary, McLeod, Walsh, and Saskatchewan). The nearby community of Capital Hill (now east Crestwood and Glenora) included Denver and Delaware Avenues.

Many developers chose to name streets after people. Sometimes, they named them after themselves: examples include Tretheway Avenue, Magrath Avenue, Holgate Avenue, Davidson Avenue, Sage Street, and Appleton Street. Other times, the names were family members, such as Ada Boulevard (wife of William Magrath), or Paul Avenue (son of Hugh Calder, developer in Calder).

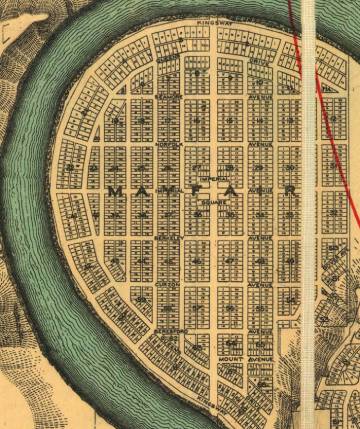

Several communities had distinctive British connotations, showing the reach of British Imperialism and colonialism, as well as the kind of newcomers the developers were trying to attract. Examples can be seen in Mayfair (which was never developed and eventually became Hawrelak Park): Curzon, Imperial, Queens Drive, Kingsway, Dover, Norfolk; and in Glenora: Connaught, Victoria, King’s Road, St. George’s Crescent, Wellington Crescent.

It is interesting to note that the names at this time appeared to be quite fluid. This map shows Mayfair in 1912 (the same year as EAM-86), but with entirely different street names!

![Edmonton, 1903 [EAM-52]](/sites/default/files/public-files/images/EAM-52-FullSize.jpg)

![Strathcona, 1907 [EAM-77]](/sites/default/files/public-files/images/EAM-77-FullSize.jpg)