Journey of the Horse is committed to preserving the rich cultural heritage of Edmonton’s Chinese history. This pop-up exhibit is a sample of what you might find at the permanent installation in the Mah Society of Edmonton building.

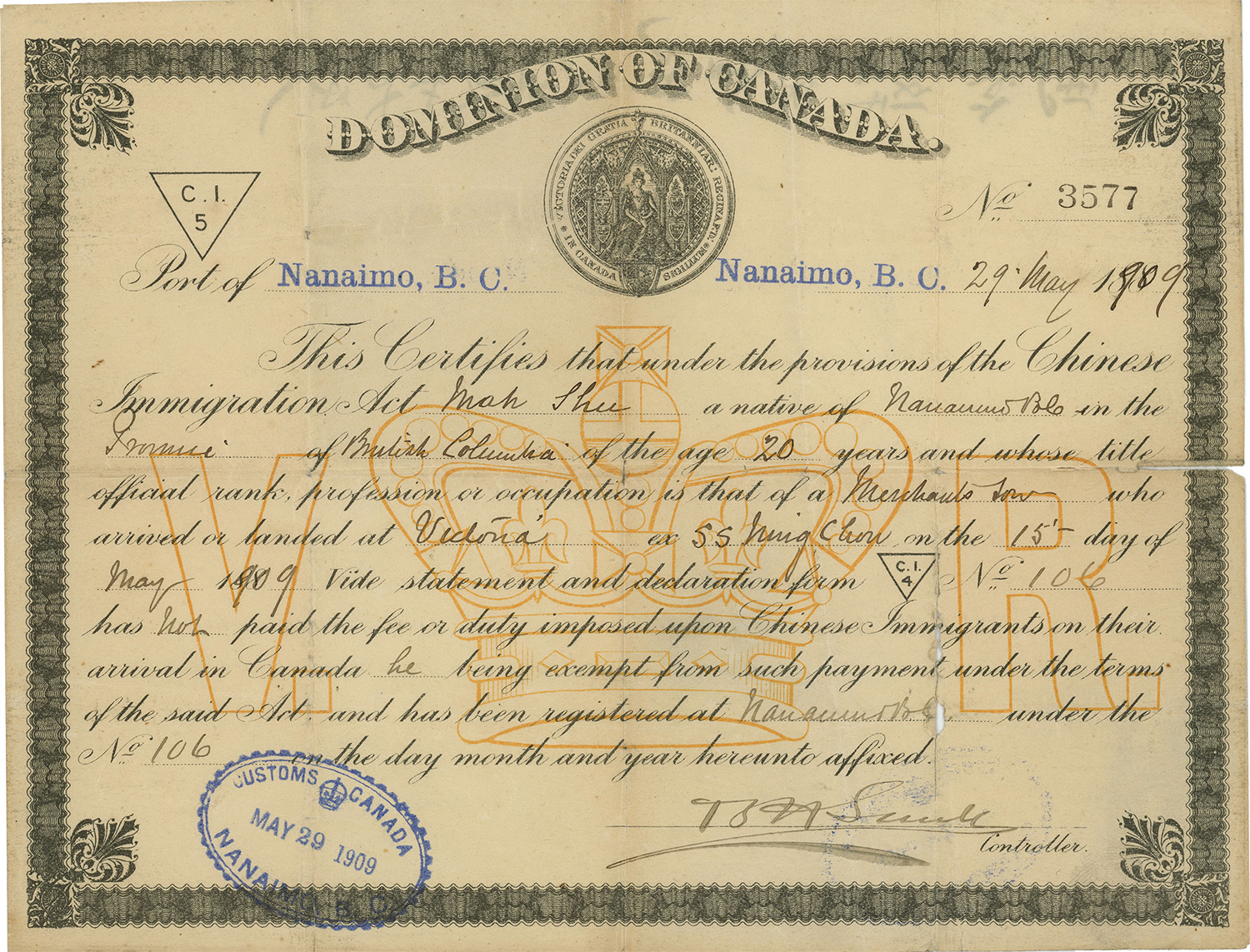

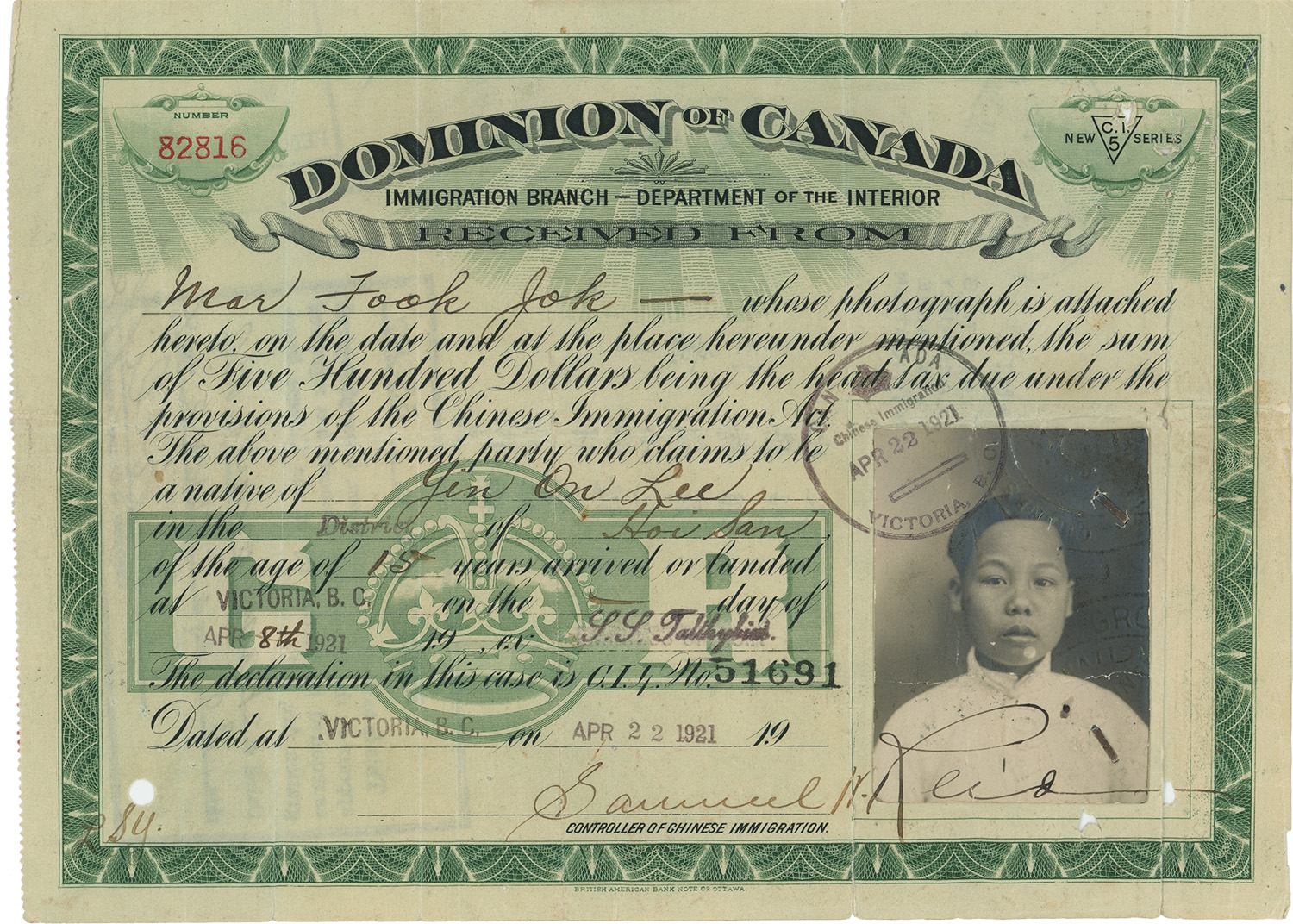

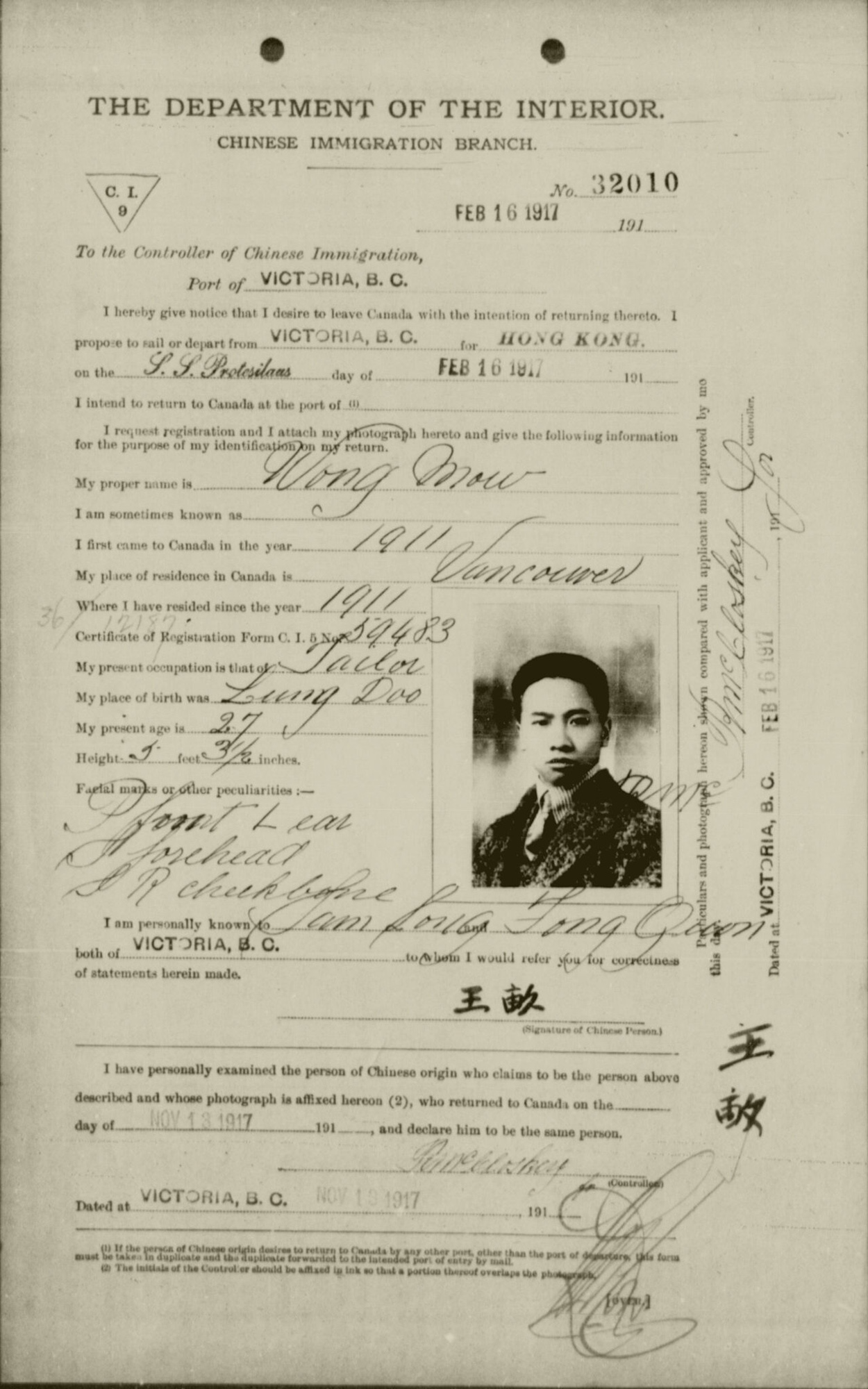

What is a C.I. (Chinese Immigration) Certificate?

After the trans-Canada railway was completed in 1885, Chinese labourers were no longer welcome in Canada. To deter further Chinese immigration, the Canadian government imposed a $50 entry fee, also known as a head tax, on all Chinese immigrants. Having not deterred enough migration, the government increased the head tax amount to $100 by 1890, and again to $500 in 1903.

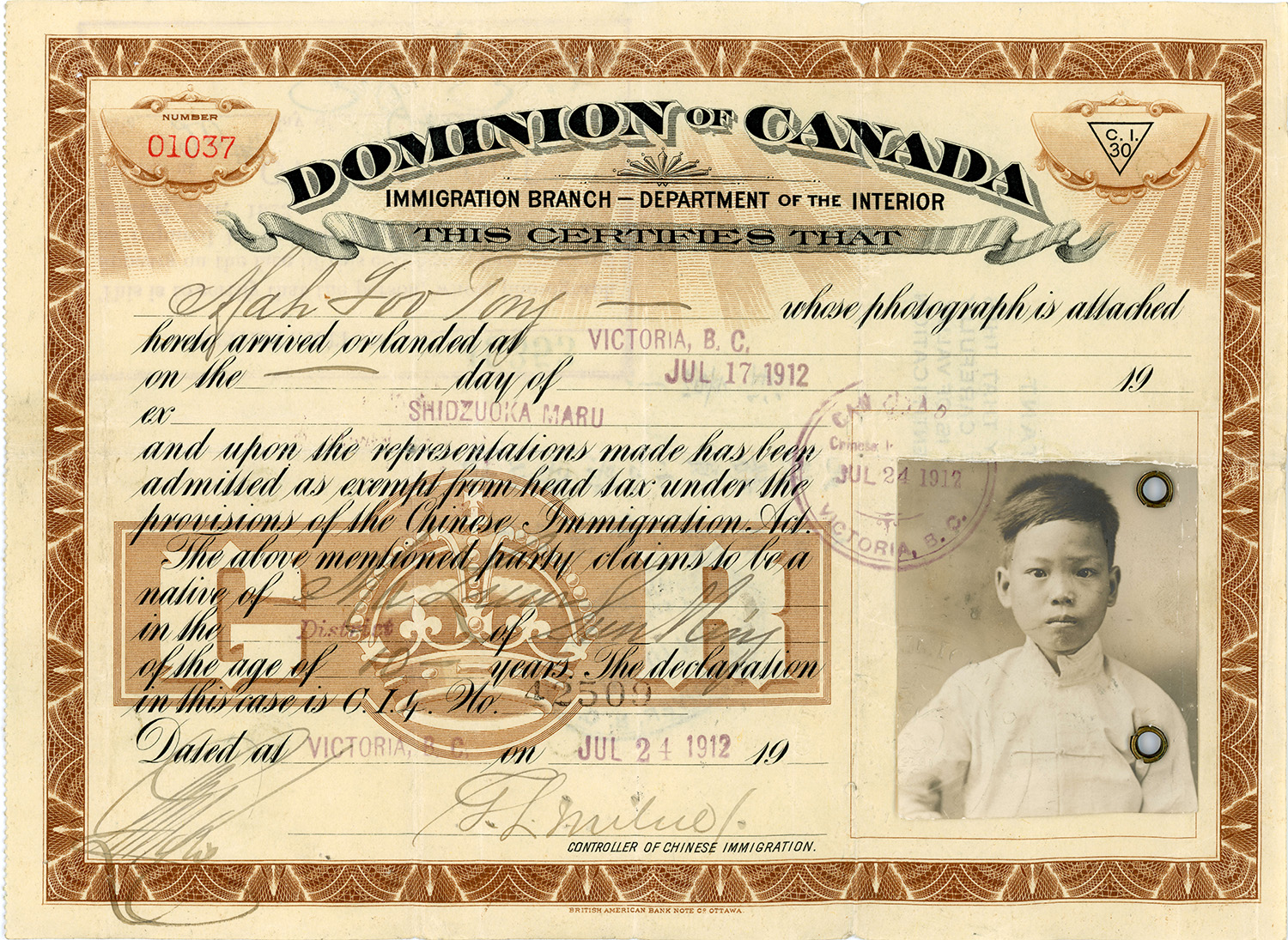

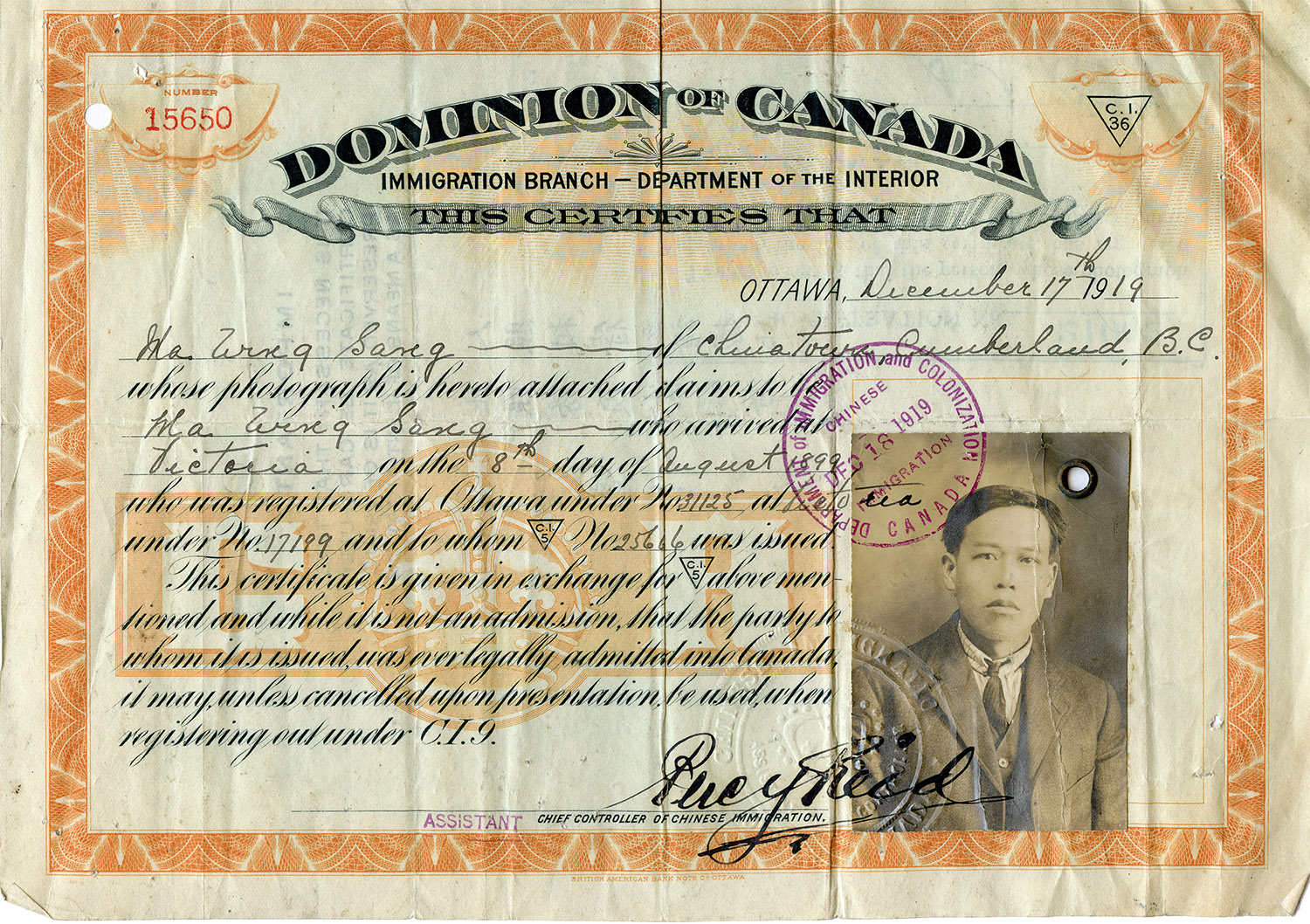

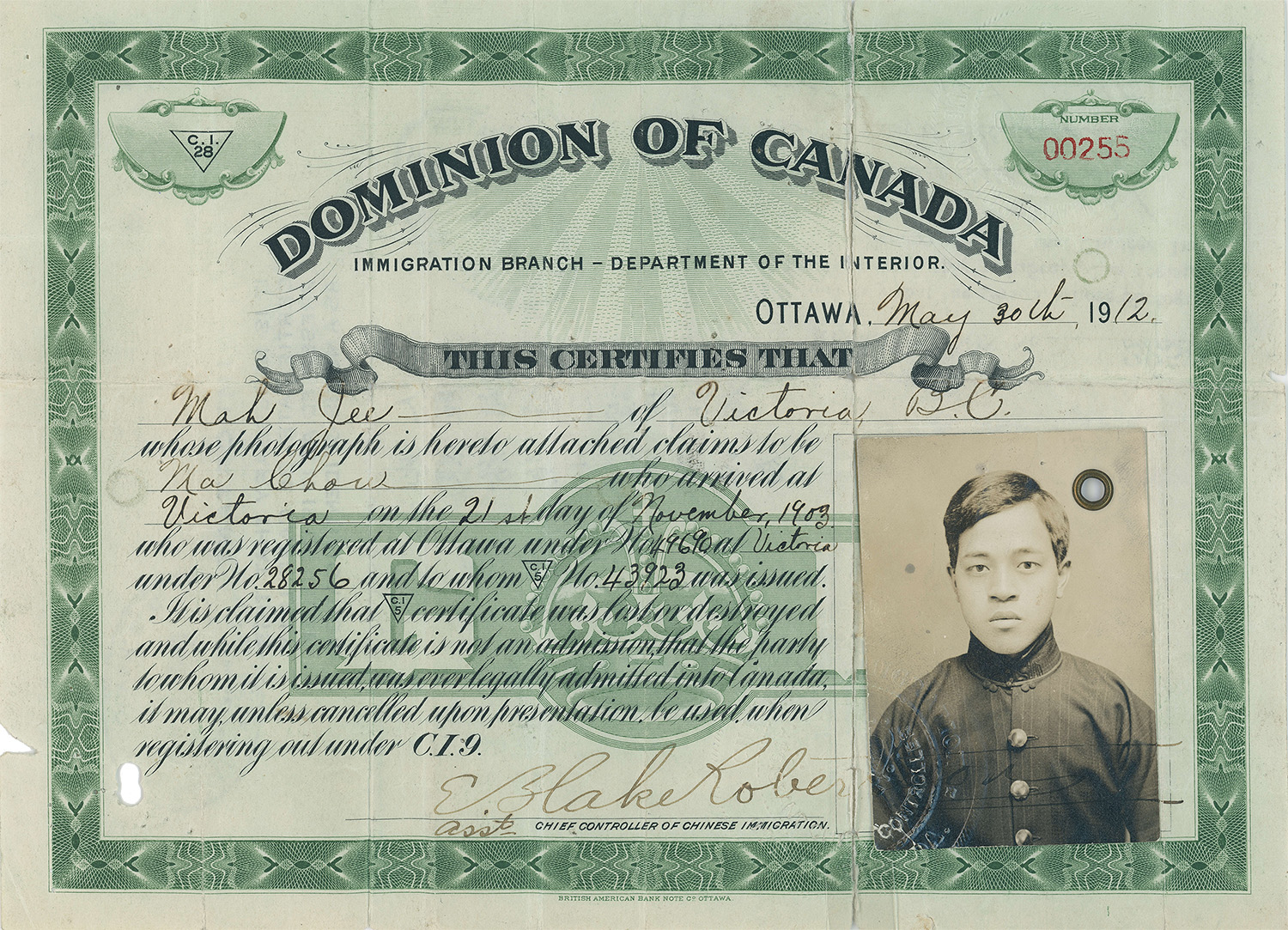

Only one original certificate was made, and it was issued to the person whom it identified. Each certificate was individually numbered and served as both an official receipt for the head tax paid and was a way to catalog the Chinese community.

It was mandatory for every Chinese person to have their C.I. certificate with them at all times. At any time, authorities could demand that the certificate be shown and failure to do so resulted in fines, detainment, or deportation. Only Chinese immigrants with a certificate were eligible for employment.

This first version of the C.I. 5 certificate was issued to every Chinese immigrant whether they paid the head tax or not. Merchants, diplomats, clergy, scientists, teachers, and temporary students were exempt from the tax.

This original design posed a challenge to officials, as they could not easily verify the identity of the certificate’s owner or determine of the tax had been paid. Around 1912 this certificate was redesigned and included a colour coded border and a photograph of the owner.

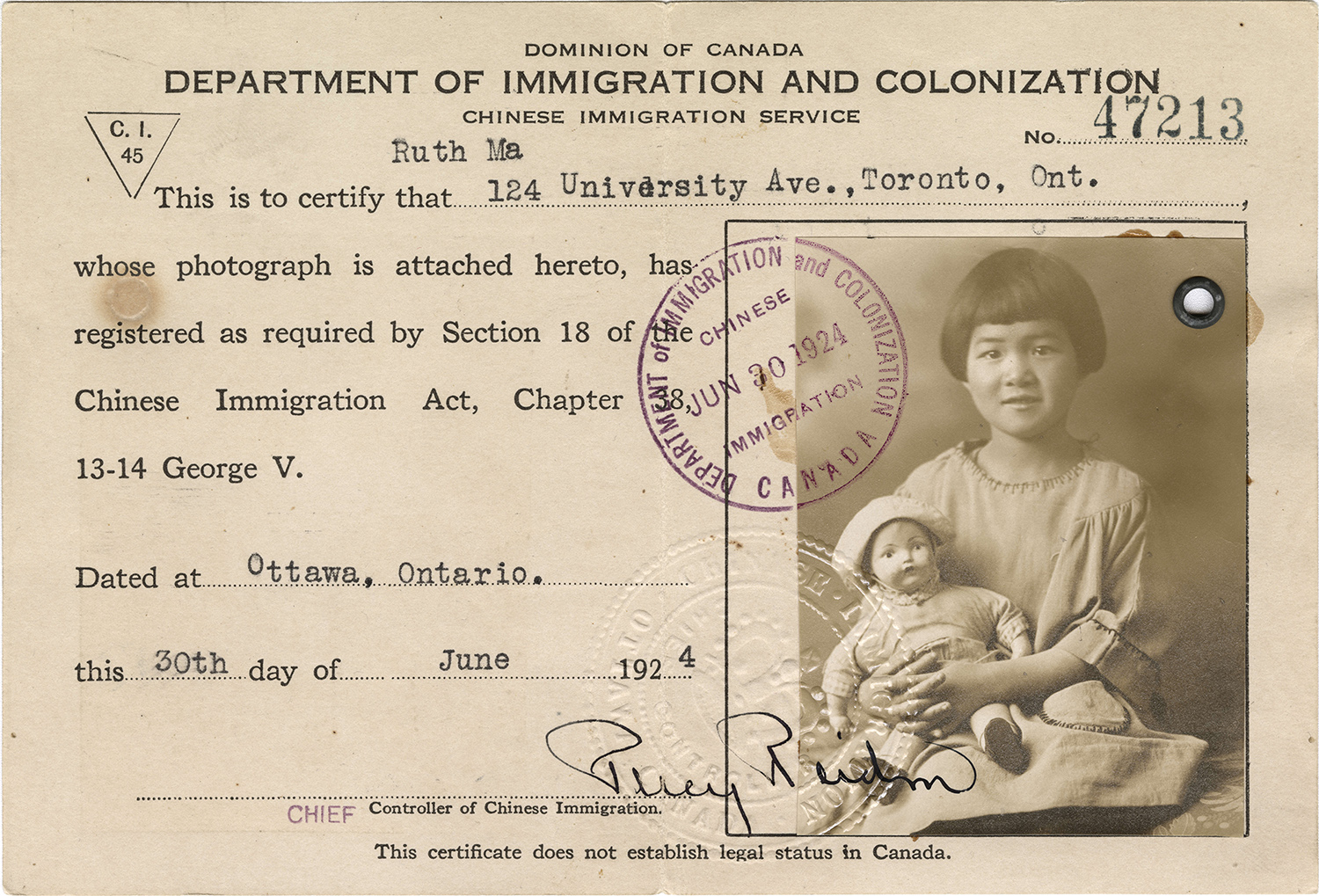

The small beige C.I. 45 card was created to solve the problem of Canadian-born Chinese children. They were problematic for the government, because they never paid a head tax and had never been documented. When the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 was enacted, all Chinese were forced to register with government officials. This new certificate was created to document the Canadian-born children.

Note the small text on the bottom of the card, “This certificate does not establish legal status in Canada.” These people, who were born in Canada, were not granted Canadian citizenship.

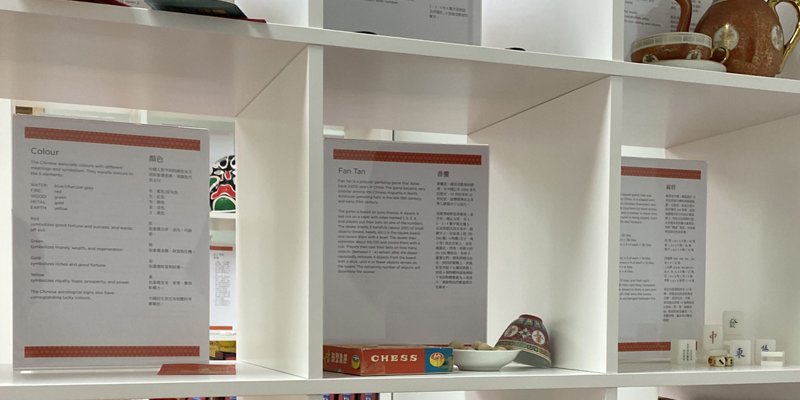

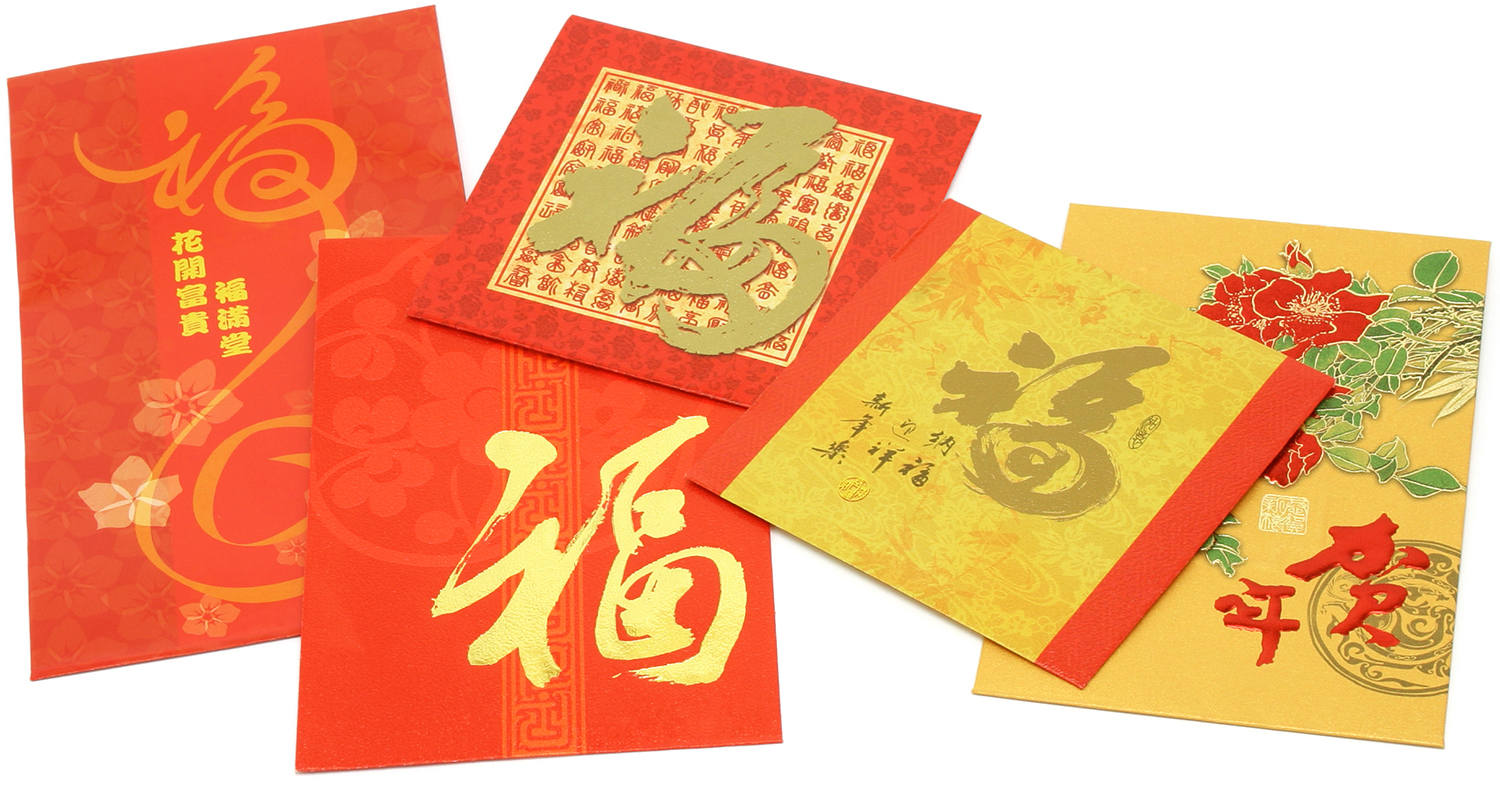

Chinese Red Envelopes

“lai see” or “hong bao” in Cantonese

The red envelope is given as a gift during special occasions such as Chinese New Year, weddings, birthdays, births, and graduations. The envelopes are usually given from those who are married to those who are unmarried, and from older to younger individuals.

Symbolism

The envelope is not about the money inside, but the red paper. The colour red is associated with prosperity, good luck, longevity, happiness, and is believed to wards off evil spirits. The envelopes are decorated with gold Chinese calligraphy and images for good luck. The colour gold is also lucky and associated with prosperity.

Custom

The amount of money inside the envelope is determined by the relationship between the giver and the receiver. The amount should be an even amount because even numbers are considered more auspicious than odd numbers. The amount should never be in multiples of fours because the Chinese word for four sounds similar to the word for death. It would bring bad luck to the receiver. The bills should be new and crisp.

The red envelope should be received with both hands, and never opened in front of the giver. That is considered polite and respectful.

The Exception

For funerals, a white envelope is used. A gift to the family of the deceased is given in a white envelope. It is called “white gold” and intended to help with funeral expenses. In this case, the amount of money enclosed should always be an odd number. According to Chinese folklore, good things come in pairs and bad things come alone. Therefore, the odd number symbolizes that death occurs once and should not be followed by another.

Upon leaving a Chinese funeral, guests receive a small white envelope that contains a piece of candy and a coin. The candy should be eaten before leaving the funeral to take away the bitter taste of death and give the guest a fresh beginning. The money should be spent that same day and is for good luck and a safe passage home.

Following the completion of the railway in 1885, jobs were scarce for everyone. Racism against the Chinese was extremely intense, and the Chinese community was relegated to hard labour and menial jobs. Higher education cost money, and combined with the racist sentiments the Chinese faced, was essentially unattainable. The Canadian government did not allow Chinese people to work as professionals, making it next to impossible for anyone from the Chinese community to prosper.

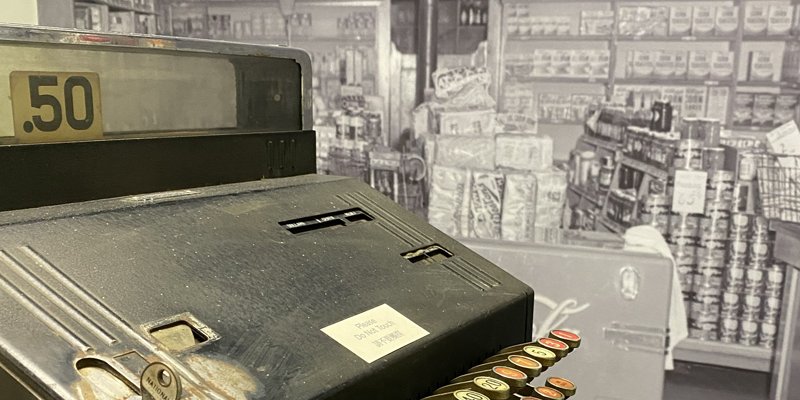

One way to make a living and possibly get ahead, was to open a small business. Owning a business, such as a grocery store, meant you could be your own boss, provide for yourself, and possibly provide jobs to other Chinese people. In this period, there were also some white store owners who refused to sell goods to members of the Chinese community. Chinese owned businesses allowed other Chinese immigrants to purchase supplies and goods for everyday life.

Before the predominance of chain grocery stores like Superstore, and convenience stores such as 7/11, Edmonton had small Chinese-owned grocery stores in many neighbourhoods. The earliest shops sold a vast array of items from basic groceries to clothing, housewares and hardware items. In some stores, there was also a lunch or ice cream counter. As large grocery and department stores emerged, the corner store adapted and sold basic groceries, such as produce, milk, candy, pop, cigarettes, magazines, etc. Many of the stores also had a mini butcher shop where fresh meat was available.

Learn More

Journey of the Horse

To learn more about the Journey of the Horse exhibit, or to get your complimentary tickets, please visit Journey of the Horse.

Mah Society of Edmonton

For more information about the Mah Society of Edmonton, visit Mah Society of Edmonton.

Chinese Immigration (C.I.) Certificates

For more information on Chinese Immigration certificates and their history, visit 1923 Chinese Exclusion.